Prime Movers at the World Cup Rally

Would you drive 16,000 miles in less than six weeks to earn the equivalent of £140,000? Yes? How about a journey across 25 countries, on unmade roads that are dusty, flooded, frozen, or muddy, with the chance of encountering wild animals, random traffic, and natural hazards, all while risking altitude sickness, with an unhealthy combination of sleep deprivation, upset stomach, and the genuine risk of death? That’s exactly what the crew of 106 specially prepared rally cars did in April 1970.

Car and Classic revisit the now legendary Daily Mirror’s World Cup Rally, which was belatedly celebrated on the 1st of May at the British Motor Museum in Warwickshire, and we dig a little deeper into the fascinating rivalry between Ford and British Leyland.

Is the car the star here?

Delayed by the pandemic by two years the event at Gaydon was hosted by the Historic Marathon Rally Group (HMRG). There was a programme of speakers which included 2nd place Brian Culcheth (Triumph 2500 pi), as well as Bron Burrell (Austin Maxi aka Puff the Magic Dragon), Claudine Trautmann (Citroen DS) and Patrick Vanson (Citroen DS) Along with a selection of replicas, tribute and original rally cars connected to that event. Several owners clubs were invited to display a handsome selection of Triumph 2500’s, Ford Escort Mexico’s, along with a neat spread of Minis.

Abingdon Connection

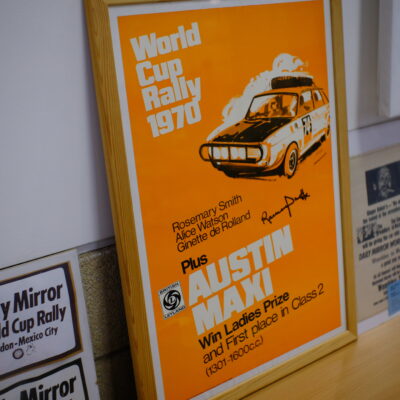

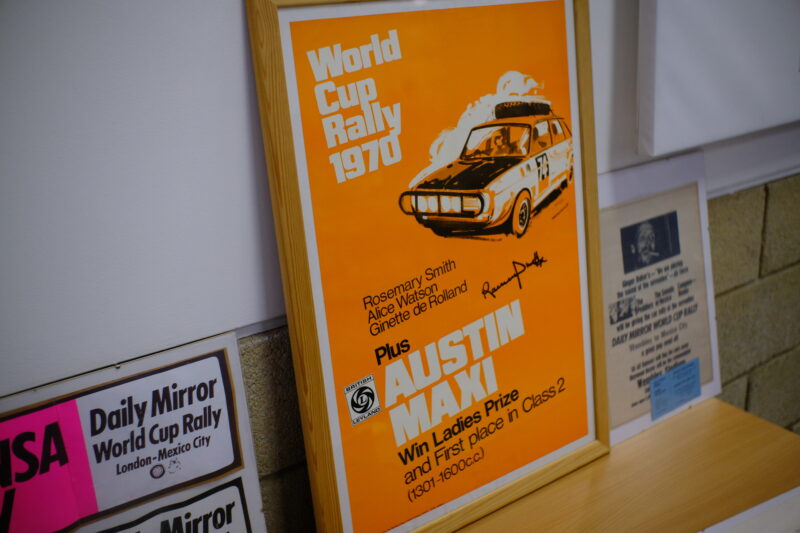

British Leyland entered the competition with three different family-oriented automobiles prepared by their Abingdon based Special Tuning Department, including four Triumph 2500 Pi’s, two Austin Maxi’s, and a Mini 1275 GT. In what Lord Stokes, BL’s chairman, believed would be a clean sweep of the event, BL also worked their magic on six BMC 1800’s ‘Landcrabs’ for private participants. Triumph had forged a successful reputation in rallying, with the TR sports cars and saloons often performing well in previous world rally stages. At the same time, Austin had also developed a formidable force with the Mini Cooper and the Landcrab had developed a reputation as a strong long-distance rally car. The new Maxi showed promise in demonstrating positive reliability during the high mileage development process and BL entered the event with a certain confidence.

This is one of the four works Triumphs entered into the event and the best known of the quartet, thanks to its second-place finish by Brian Culcheth and Johnson Syer. It was extensively used in subsequent events by Culcheth before being rebuilt towards the end of 1970 but never seriously rallied thereafter. BL often scrapped their cars after their use, but somehow this example has survived and serves as a monument to the 2500’s greatest achievement.

Sister car to Culcheth’s car, this car was sold off by BL soon after Paddy Hopkirk, Tony Nash and Neville Johnston piloted it to 4th place. It was sold off and used as a privately entered competition car for several years until it was involved in an accident at an event. It still retains a 1977 road tax disk, which suggests it has been kept in storage since then, but will no doubt be restored to its former glory.

A neat addition to the 1970+2 event was this 1974 London–Sahara–Munich World Cup Rally entrant. That rally was to replicate the World Cup football theme, this time cars travelling from London to Germany, via the Middle East, Russia and across to Munich. The ambitious race was dampened by Middle Eastern conflicts and the subsequent fuel crisis. Just 69 entrants were registered to drive the 10,975 miles across 14 counties and only 19 cars qualified as finishers. This V8 powered Morris Marina driven by John Hemsley and John Skinner but was forced into retirement during the event.

When the FWD Austin Maxi was launched in the spring of 1969, BL management was insistent that the car should be developed for the rally, which was in its planning stages. After ruling out the Range Rover as a prospective candidate, the BMC 1800’s mechanical resemblance to the Maxi made committing to a new model a little easier. A permanent exhibit at the museum, it was driven by Gavin Thompson, Nigel Clarkson and HRH Prince Michael of Kent. The Janspeed prepared Maxi, unfortunately, withdrew following a crash in Brazil.

All of the rally prepared Austin Maxis lost their useful 5th door and were converted to saloons for rigidity reasons. The car was close to the production version, with additional bracing put around the subframe to help isolate vibration and harshness.

The privately entered Austin Maxi of Tish Ozanne, Bron Burrell and Tina Kerridge was forced to retire after sliding off the track in Argentina, however, Bron and Tina are still very active in using ‘Puff the Magic Dragon’ and regularly participate in historic rally events to this day. Bron is one of the primary players in the event’s planning.

A replica of John Handley’s and Paul Easter’s Mini 1275 GT. While the 1275 GT was a comparatively new release, everything learned from the Mini Cooper’s 8 years of competitive history was applied to the car. Envisaged as a ‘Hare’, to the other BL’s bigger ‘Hounds’, the 1275 GT was the fastest BL car on the rally but never made it across the Atlantic. The same car managed to perform better in the hands of Paddy Hopkirk a few months later, finishing second in the Scottish rally in June 1970.

Enter the Escort

Ford however had other ideas for BL’s planned domination. Encouraged by the success of the Cortina as a rally car, their recently launched Escort was a modern pan-European developed family saloon with a strong light body and the ability to house many different engines. In the UK Ford up to this point had been playing the second fiddle to BMC’s ever-increasing portfolio, but their global outreach, contrasting to BMC’s diminishing returns suggested that there was a gradual shift on the cards. Ford entered seven works prepared cars, all Escorts with twin-cam engines.

The winning car, FEV 1H, is possibly the most renowned Ford Escort of all time, originally piloted by the legendary Hannu Mikkola and Gunner Palm. It is the centrepiece of the Ford heritage collection, having performed impeccably during the gruelling latter stages of the event and finished an impressive one hour ahead of the Culcheth Triumph.

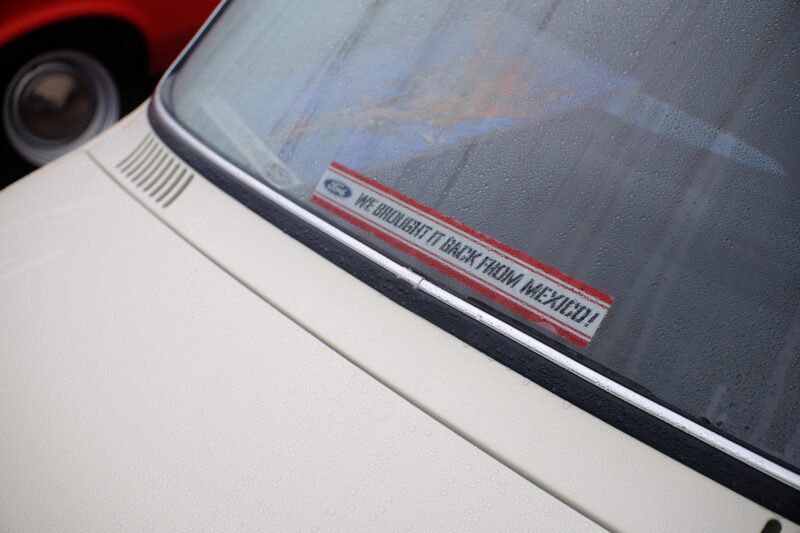

Fully aware of the Escort’s place in rally history, Ford pulled out another marketing trick in 1993 by building a replica of the original car for the 25-year anniversary re-run of the 1968 London to Sydney rally. Both Mikkola and Palm came out of retirement to win the London-Mexico Retrospective Rally in 1995, giving the car a pedigree of its own. It has been involved in a few mishaps as part of the rally car package, including a crash at Goodwood in 2009, but the Ford Heritage workshop rebuilt it and it now sits alongside the original in the collection.

Never one to miss a trick, Ford capitalised on their success on the rally and got to work on developing a Mexico edition of their Escort. The original idea was to utilise the planned 1600 GT and badge it as the Mexico, but needing a car for promotional purposes they used a completed RS1600, sprayed it Sunset Red and hand painted the white side stripes. Retained by Ford, the car was used to train Ford Rally Sports mechanics and is believed to have spent a few years as Roger Clark’s daily driver in the ’70s.

One Escort that didn’t make it out of Europe was Colin Malkin and Richard Hudson-Evans’s car, which was hit by a truck in Yugoslavia. This replica of that car is a regular participant in the classic rally scene, having seen several long-distance rallies in the hands of its owners, including the Peking to Paris motor challenge and the Adriatic Rally.

While Ford was fully occupied with nurturing the Escort as their works rally car, it was inevitable that the newly launched Capri which shared many of the Escorts characteristics would be unleashed on the rally stages. Better known as a tarmac racer, two cars competed under private entry guises. This is the Team Dunton car, an entry from Ford’s research and development team driven by Brian Peacock and Dave Skitteral. Although it never finished the event, this recently restored car is believed to be the only original surviving car in the world to have competed in both the 1970 and 1974 World Cup Rallies.

Kick-off at Wembley

The cars were flagged off by Sir Alf Ramsey on a sunny day on April 19th, 1970, and 106 cars left Wembley Stadium to compete in what was considered the toughest rally event in the world. The event, which was organised by the Daily Mirror, was likely inspired by the 1968 London-Sydney Marathon and was organised to commemorate the 1966 FIFA World Cup in London and the approaching 1970 FIFA World Cup in Mexico. With its footballing credentials intact, the event was dominated by British cars and entrants, with Jimmy Greeves behind the wheel of one of the works Escorts.

Continental Drifts

The route from London to Mexico includes a succession of primes (special stages) via France, Germany to Sofia, Bulgaria, and then through Italy and Spain to Lisbon, Portugal. From there the cars would be shipped across the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, then driven across to Uruguay and Argentina, working their way up to Central America concluding at the Aztec Stadium in Mexico City.

Organisational Skills

The organisation needed was colossal, with everything from local traffic management control to the storage of tyres needing pin-point planning, all carried out during the era of teleprinters and analogue phone calls. In what was considered a significant challenge for the crews, team chiefs, and mechanics, an information centre was set up in the foyer of the Daily Mirror Building in Holborn Circus, consisting of tireless teams manning phones, which not only processed competitor times and information but also served as a point of contact for worried relatives.

Big Players Flexing Their Muscles

Other significant manufacturers Peugeot, Moskvitch and Hillman, which were driven by a mix of sponsored factory teams and private participants. A deeper glance over the list of 106 entrants, include cars such as the Datsun 510, Toyota Corolla and Porsche 911 demonstrating the power of rallying as a marketing tool, however, it wasn’t all long-distance rally proven cars, a privately entered VW beach buggy and a Rolls Royce Silver Cloud were also listed as starters.

A contentious issue was Citroen’s involvement in the competition. Listed as private entries, all three cars were prepared and maintained by Citroen and therefore would normally be classified as works rally cars. Placing these cars as privateers meant that the owners stood a better chance of obtaining the private entrant’s prize money, which some felt deprived the genuine private entries of the opportunity. None of the cars were finished in the factory colours, yet the drivers were recognised as works drivers. This is a replica of Robert Neyret and Jacques Terramorsi’s car, which withdrew in Lima.

After the considerable honour of winning the London to Sydney Marathon in 1968, the recent internal changes within the Chrysler organisation meant that there was no interest by the company to include any works cars. It was up to the resources and dedication of the four privately entered cars to try to reclaim that crown. They were very similar to Andrew Cowan’s winning car and one out of the four did end up finishing the event, suggesting that there was still potential in the ability of the design.

Preparation Into the Unknown

Representatives from both BL and Ford spent time in Europe and South and Central America in preparation for the rally, taking pace notes, photos, and cine video to assess the probable traps and hurdles. The shifting weather patterns, as well as monitoring the roads and traffic situation, as well as observations ranging from two-plank bridges to 10-foot snowdrifts, had to be taken into account. Even the opening leg from London down to Dover wasn’t without incident, with several competitors picking up speeding tickets!

On to Europe

When the vehicles arrived in Europe for the first five primes of the rally, which lasted six days, some of the cars felt the effects of faltering reliability. While the majority of the vehicles handled the relatively flat roads and manageable stages with ease, a couple of the works Escorts began to experience small teething troubles, while the journey to Sofia, at least for the BL cars, remained largely uneventful. Problems were encountered in the former Yugoslavia, as it was the only country where the police had not managed the traffic, which resulted in several accidents. However, it was the routes across over to the west of Europe that saw almost a third of the entrants retire. A toll on suspension components and engine setbacks, due to the fast pace of the European stages were mostly to blame. After the initial hiccups, the Ford Escorts eventually found their beat and their reliability started to improve by the mile. The Triumphs fared well too, fast and stable given the right conditions, the Maxi’s were not quite as fast but were guided by careful drivers which meant that a minimum of repair work was needed at the end of each prime. Driver fatigue was beginning to set in, and the Triumph’s were particularly affected. The 3-man cars’ firmer suspension meant that there were few opportunities for the third driver to get some rest.

Crash-landing in South America

At the end of the European leg in Lisbon, some drivers took well-earned breaks, as the cars were shipped across the Atlantic as the competitors were flown to Rio de Janeiro. The going was about to get even tougher but both BL and Ford managed to place themselves in the top ten competitors with their works cars, with Citroen making up the remainder of the places. With 13 designated stages, with some of the primes covering up to 370 miles, increased the uncertainty of running out of fuel, the continuous pounding of the tyres, suspension as well as the rest of the running gear would be the ultimate test of endurance. BL favoured the heavy sidewall tyres, which had been well proven during the London to Sydney event but were offset by poor road holding. The Escorts needed more regular tyre changes but this seemed to be an inconvenience worth suffering, as the cars made astonishing pace. Unlike BL, who opted for a three-man crew, the Ford works cars only used two occupants. Over a 16,000 mile distance, the difference in weight soon became apparent as the race progressed too. Also by adding that third person, the potential for conflict amongst the crew was obviously increased, aggravated by fatigue and discomfort.

Generosity and Tragedy

Over the course of the first week in South America, the number of cars still competing had whittled down to 54, almost half the number that started in London. The larger budgets and better resources of the works teams really start to come into their own. Casualties were rife, including one of the four Russian Moskvitch’s crashing down an embankment, but despite its shattered state, still managed to hobble onto the control at La Paz. The Datsun also suffered what would have been considered terminal damage but again nursed back to base. Sadly, there was also a fatality of one of the Citroen drivers, which underlines the dangers that the teams faced. As well as tragedy, there were many instances of camaraderie, with drivers often helping each other at the forfeit of penalty points. There was also an instance of the young student competitor in a VW Beetle, who had run out of money and was helped out thanks to a whip-round amongst the competitors.

BL Verses Escort Outcome

The rally was eventually conquered by Ford, with Hannu Mikkola being declared the winner of the event. It established the Finn as a dominant force in rally sports, which was later cemented by his involvement with 1980s achievements with Audi. Triumph managed to grab the second place, courtesy of Brian Culcheth followed by Rauno Aaltonen, another Finn in another works Escort. Just 23 cars finished the race.

So how did Ford manage to beat BL? Despite a little uncertainty during the initial stages of the rally, the reliable 1800cc engines sourced from the Cortina were the core reason. The combination of their rigid rally cages, which also strengthened the suspension gave the already good cornering skills a helping hand in terms of their handling. Ford’s immeasurable worldwide coverage gave the Escort an edge over BL, with common parts being sourced without too much trouble even in the remotest of towns. Furthermore, the Escorts were light cars with a minimum of inboard spare components, which was supported by the Fords’ employment of a two-man crew. All the other BL works cars had three crew members, with the exception of Culcheth in his Triumph, who shared his cabin with co-driver Johnstone Syer. Considering his second place finish, it certainly suggests that this was the better option.

However, BL still emerged as an able competitor to Ford, with two Triumph’s in the top five and five other private entrants in BL cars completing the event. Ford went from strength to strength with the Escort, as it dominated the scene throughout the ’70s. But what of BL? Was the potential fulfilled? The answer lies in the ailing BL organisation, with company politics and economic restrictions playing a large part, but the need for a large long-distance rally car was vetoed for outright speed and manoeuvrability. BL did continue to develop the smaller Triumph products such as the Dolomite and TR7 for rally sports with reasonable success, but the advantage had already been taken by its arch-rival. Ford also fully capitalised on the success of the event, and their marketing department went into full steam after the win. This obvious but clever piece of marketing may go some way into explaining why the MK1 Escort is now firmly established in Ford circles as a very desirable car.